Although there has been a church at Fairford since at least 1125, only fragments of an early building now remain, having been incorporated into the magnificent Late Perpendicular church of St Mary the Virgin that we see today. The rebuilding of the church was started by John Tame in the early 1490s after been given permission by the Bishop of Worcester to dismantle the existing church. As Tame’s fortune was acquired through the wool and cloth industry, St Mary’s can be counted as among a number of so-called ‘wool’ churches built in the Cotswolds in the medieval period. The new church at Fairford was consecrated in a ceremony presided over by the Bishop on 20 June 1497, an event marked by a painted Consecration Cross on the wall of the chancel near the vestry door. Although structurally complete, the church was still far from finished at this point and at the death of John Tame in 1500 his son Edmund Tame undertook to complete the work. At about this time work commenced on the production of 28 painted glass windows that would make up a stunning visual account of the Bible story from Adam and Eve through to the Last Judgement and would provide instruction as well as illumination, in both senses of the word. The story that these windows tell also reveals the central role of the Virgin Mary to pre-Reformation English liturgy. Fairford’s windows remain the most complete set of medieval church windows in the country and are therefore of national importance.

St Mary’s church, as rebuilt by the Tames, consists of a central nave flanked by two aisles that each originally terminated in a side chapel. On the north side the Lady Chapel contains the tomb of John Tame and his wife Alice. A monumental brass depicts the pair and the tomb is now surmounted by a beautifully carved wooden screen added in about 1520 and which serves to separate the chapel from the chancel. Also in the Lady Chapel is a chest tomb tomb with life-size stone effigies of Roger Lygon and his wife Katherine, widow of the grandson of John Tame. Beneath the floor of the chapel is a vault containing the remains of Sir Edmund Tame and his wives, Agnes and Elizabeth, all commemorated by a brass on the chapel’s north wall.

Also in the Lady Chapel is a chest tomb tomb with life-size stone effigies of Roger Lygon and his wife Katherine, widow of the grandson of John Tame. Beneath the floor of the chapel is a vault containing the remains of Sir Edmund Tame and his wives, Agnes and Elizabeth, all commemorated by a brass on the chapel’s north wall.

The Corpus Christi Chapel on the south side of the church is of less interest but it does have a fine marble monument to Sarah Ready who died in 1731. The almost complete set of wooden screens in the choir is particularly fine and date from around 1520. The wooden stalls are thought to date from around 1300 and may possibly have come from Cirencester Abbey following its dismantling during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in about 1540. The choir also contains a set of 14 misericord seats that incorporate carvings showing various forms of sin or strife, obviously done with a moral intent. The almost perfect symmetry of the Church building plan was spoiled at a later date by the addition of a sacristy or vestry beyond the Lady Chapel, however this does little to mar the visual effect of what is one of the most beautiful churches in the Cotswolds.

Now situated in the middle of Tame’s rebuilt church, the lower portion of the tower is the oldest part of the building. The later work to increase the height of the tower is apparent from the exterior where a change in the stonework and shape of the corner buttresses indicate the newer building. On the interior columns that form the base of the tower can still be seen traces of late medieval wall paintings including several figures (one of which may be St Christopher) and simple patterns. The roof of the church is supported by a total of 69 stone angels that adorn the corbels of the wooden roof beams. There are a number of wall-mounted monuments to past Fairford citizens including three to the Oldisworth family.

The exterior of the building contains a wealth of decoration and sculpture of great interest. Some of the decoration reflects the patronage of Fairford’s church and includes the gryphon and bear and ragged staff of the Earl of Warwick, an early lord of the manor. The coat of arms of John Tame, consisting of a Wyvern and a lion, can be seen above the door into the church from the porch. A series of curious figures adorn the stringcourse below the embattled parapet that runs all around the outside of the church.  These sculptures include a dragon, a lion, a dog, a sheep and, most charming of all, a boy in the act of climbing down from the parapet (right). In addition to these sculptures are figures of a more serious nature including the Christ of Pity at the west end of the church and four fierce guardians standing sentry at the four corners of the tower.

These sculptures include a dragon, a lion, a dog, a sheep and, most charming of all, a boy in the act of climbing down from the parapet (right). In addition to these sculptures are figures of a more serious nature including the Christ of Pity at the west end of the church and four fierce guardians standing sentry at the four corners of the tower.

The graveyard of St Mary’s contains some fine examples of Cotswold tombs including several that have Listed Building status as being of historical and architectural importance. There are several examples of large chest tombs, some of them surmounted by semi-circular spiralled slabs once thought to represent bales of wool. One of the earliest monuments in the graveyard is that of Valentine Strong who died in 1662 and was a well-known Cotswold stonemason and architect who built Fairford Park and Lower Slaughter Manor among other buildings. There is also a fine set of three listed tombs of the Morgan family situated outside the end of the Corpus Christi Chapel.  Among the grand and ancient tombs in the churchyard is a delightful stone sculpture of ‘Tiddles’, a much-loved Church cat who ‘guarded’ the church and its precincts from 1963 to 1980.

Among the grand and ancient tombs in the churchyard is a delightful stone sculpture of ‘Tiddles’, a much-loved Church cat who ‘guarded’ the church and its precincts from 1963 to 1980.

Chris Hobson

Further reading:

The Great Storm of 1703 https://www.fairfordhistory.org.uk/the-great-storm-1703/

The buildings of England. Gloucestershire 1: The Cotswolds by David Verey and Alan Brooks. London: Yale University Press, 2002

Fairford Church and its stained glass windows by Oscar G Farmer. Various editions, 1928-1968

The medieval stained glass of Fairford parish church by Sarah Brown and Lindsay MacDonald. Revised pbk edition. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2007

Bryworth Bridge near Fairford, 2006

Bryworth Bridge near Fairford, 2006

Farmor’s School opened as Fairford Free School on 24th November 1738. The school’s first schoolmaster was Jacob Kuffeler, a descendant of an ancient and prominent Dutch family. The building cost £543.8s, and consisted of a schoolmaster’s house and 2 classrooms with cellar and outbuildings including a brewhouse and a well in the rear yard. There had previously been several legacies to provide education in Fairford. In 1670 Lady Jane Mico founded a charity to provide apprenticeships for ” 4 poore Boys”, and in 1701 Mary Barker, daughter of Andrew Barker, Lord of the Manor of Fairford, left money for investment to raise funds for teaching poor boys to read and write. Later Elizabeth Farmor, Andrew Barker’s granddaughter, left £1000 in her will, specifically to build a school and pay a schoolmaster. The school originally had accommodation for 60 boys, aged between 5 and 12, and if Fairford children did not fill all the places, numbers could be made up from the surrounding villages. Boys could be “turned away” for bad behaviour, and left school to start work at the age of 12.

Farmor’s School opened as Fairford Free School on 24th November 1738. The school’s first schoolmaster was Jacob Kuffeler, a descendant of an ancient and prominent Dutch family. The building cost £543.8s, and consisted of a schoolmaster’s house and 2 classrooms with cellar and outbuildings including a brewhouse and a well in the rear yard. There had previously been several legacies to provide education in Fairford. In 1670 Lady Jane Mico founded a charity to provide apprenticeships for ” 4 poore Boys”, and in 1701 Mary Barker, daughter of Andrew Barker, Lord of the Manor of Fairford, left money for investment to raise funds for teaching poor boys to read and write. Later Elizabeth Farmor, Andrew Barker’s granddaughter, left £1000 in her will, specifically to build a school and pay a schoolmaster. The school originally had accommodation for 60 boys, aged between 5 and 12, and if Fairford children did not fill all the places, numbers could be made up from the surrounding villages. Boys could be “turned away” for bad behaviour, and left school to start work at the age of 12.

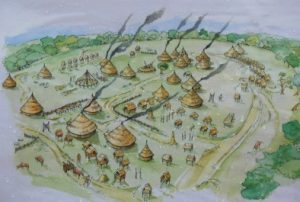

Evidence of fence posts and enclosures also exist. Within the settlement were the vestiges of a large number of four-post structures. These are thought to have been small grain stores as Spelt and Emmer wheat seeds where found in the post holes. Analysis of the Iron Age evidence continues.

Evidence of fence posts and enclosures also exist. Within the settlement were the vestiges of a large number of four-post structures. These are thought to have been small grain stores as Spelt and Emmer wheat seeds where found in the post holes. Analysis of the Iron Age evidence continues. Roman:

Roman: settlement at Horcott is one of the largest discovered in the region. There were two types of buildings; rectangular post-built halls and sunken-featured buildings or Grubenhausen (‘Grub Huts’). The sunken-featured buildings, consisting of a building raised on four large posts at each corner of a rectangular hole in the ground, may have been workshops or simple dwellings. The rectangular halls were thought to be houses.

settlement at Horcott is one of the largest discovered in the region. There were two types of buildings; rectangular post-built halls and sunken-featured buildings or Grubenhausen (‘Grub Huts’). The sunken-featured buildings, consisting of a building raised on four large posts at each corner of a rectangular hole in the ground, may have been workshops or simple dwellings. The rectangular halls were thought to be houses.

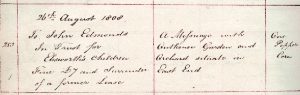

The Society has been very fortunate to have been donated a unique historical document relating to Fairford property and people of the 18th and 19th centuries. The foolscap-size notebook is titled “Lifehold Estates belonging to John Raymond Barker Esq” and was donated to the Society by a Fairford resident, whose late husband once worked for the Ernest Cook Trust. The 46-page document records the creation and renewals of leases relating to John Raymond Barker’s property in Fairford, the earliest being dated 1768 and the latest 1884. Over 120 leases are recorded and the details given add greatly to our knowledge of Fairford’s residents and property ownership during the Barker and Raymond Barker family’s time as landlords. Some of the entries are quite revealing; for example the entry for Jonathan Wane’s lease of a house in Milton End on 26 May 1803 gives him the option of paying either four shillings for rent, or just one shilling and “2 couple of fat hens”. In fact poultry seems to have been an alternative form of currency in the 19th Century as six other lessees were given the option of paying part of their rent in chickens!

The Society has been very fortunate to have been donated a unique historical document relating to Fairford property and people of the 18th and 19th centuries. The foolscap-size notebook is titled “Lifehold Estates belonging to John Raymond Barker Esq” and was donated to the Society by a Fairford resident, whose late husband once worked for the Ernest Cook Trust. The 46-page document records the creation and renewals of leases relating to John Raymond Barker’s property in Fairford, the earliest being dated 1768 and the latest 1884. Over 120 leases are recorded and the details given add greatly to our knowledge of Fairford’s residents and property ownership during the Barker and Raymond Barker family’s time as landlords. Some of the entries are quite revealing; for example the entry for Jonathan Wane’s lease of a house in Milton End on 26 May 1803 gives him the option of paying either four shillings for rent, or just one shilling and “2 couple of fat hens”. In fact poultry seems to have been an alternative form of currency in the 19th Century as six other lessees were given the option of paying part of their rent in chickens! John Keble’s house in Fairford which was called Court Close at the time and in which John Keble senior lived all of his married life.

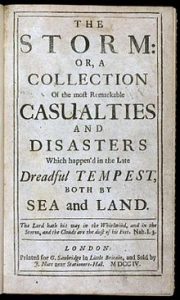

John Keble’s house in Fairford which was called Court Close at the time and in which John Keble senior lived all of his married life. The Great Storm of 26 November 1703 was one of the most powerful and destructive storms in recorded English history. The storm came in from the Atlantic and cut a swathe of destruction across southern and central England and out into the North Sea. In London about 2,000 chimney stacks were blown down and at least 1,500 men were lost at sea as many ships, including the Royal Navy’s entire Channel Squadron, were sunk. One warship was blown from Harwich all the way to Gothenburg in Sweden before it was able to sail back to England. There was extensive flooding in the West Country where hundreds of people and thousands of livestock were drowned in the Somerset Levels. Other instances of destruction include about 400 windmills which were destroyed, about 4,000 oak trees in the New Forest blown down, and the collapse of the first Eddystone Lighthouse.

The Great Storm of 26 November 1703 was one of the most powerful and destructive storms in recorded English history. The storm came in from the Atlantic and cut a swathe of destruction across southern and central England and out into the North Sea. In London about 2,000 chimney stacks were blown down and at least 1,500 men were lost at sea as many ships, including the Royal Navy’s entire Channel Squadron, were sunk. One warship was blown from Harwich all the way to Gothenburg in Sweden before it was able to sail back to England. There was extensive flooding in the West Country where hundreds of people and thousands of livestock were drowned in the Somerset Levels. Other instances of destruction include about 400 windmills which were destroyed, about 4,000 oak trees in the New Forest blown down, and the collapse of the first Eddystone Lighthouse.