FAIRFORD WILLS

Old wills can often reveal historical information not found anywhere else. This is especially true with regard to family relationships, property ownership and the testator’s character and occupation although it should be remembered that wills are often written to a standard legalistic formula and that testators may have left legacies not included in the will. Some wills are very brief and provide very little useful information but others can be very lengthy and very revealing. Many wills of the 17th and 18th centuries were accompanied by inventories which listed the household goods, money and credits of the deceased. These often include a lengthy list of the goods (furniture, clothes, bedding, utensils, etc) together with their estimated value. Some inventories list the goods room by room thereby suggesting the size and sometimes even the layout of the deceased’s house.

This series will consist of selected details from some of the almost 600 wills and inventories of Fairford residents dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries that have been collected and transcribed. These wills can be found in the collections of the National Archives and the Gloucestershire Archives. Those in the National Archives are of people whose wills were proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in London and date from 1384 to 1858. They are the wills of the wealthier people, often those who owned property in more than one county. The collection of wills in Gloucestershire Archives are of those of less wealthy people and date from 1541 to 1858. In 1858 the probate of wills was transferred from the ecclesiastical courts to the civil courts. The wills from the Prerogative Court of Canterbury are copies of the original but most of the Gloucestershire Archive wills are originals. The handwriting can sometimes be very difficult to read but with enough practice most, if not all, of the content can be transcribed. Unfortunately some people died without making a will but the Gloucestershire Archives collection includes printed forms which give basic details of the execution of intestate wills. Until education became compulsory in the 19th Century many of the early testators were unable to read or write so signed their names with an ‘X’ or some other mark. Even those who could write rarely wrote out their own will, usually a friend or a solicitor or his clerk would do the writing. A small number of wills relating to Fairford residents or former residents have also been collected from the online collections from other counties, particularly Oxfordshire and Wiltshire.

Many of these wills provide valuable information that adds to our knowledge of Fairford history while others are interesting for a variety of reasons including: language and terminology; examples of great wealth or great poverty; details of property (both real, i.e. buildings and land, and personal, i.e. goods and chattels); and evidence of religious beliefs. Up until the 19th Century Fairford life was predominantly based on agriculture and the wills reflect this. However, the Fairford wills represent a wide range of occupations and trades.

They are also useful in determining family relationships, especially when, as with the Betterton family for example, there were several people of the same forename and surname living in Fairford at the same time. Various themes can be detected in the wills of Fairford residents. For example, in the earliest period (16th and 17th centuries) it was common for livestock, particularly sheep, to be bequeathed to family and friends. In the 17th to the 19th centuries furniture, particularly beds and bedding, were common bequests. Craftsmen often bequeathed their tools to sons – and occasionally daughters – in the hope that they would carry on their business. Those who were in trade, such as shop keepers, often bequeathed their ‘stock in trade’ to their relatives. These and other themes will be featured in this series of Fairford Wills.

Click here for

BROWNE, Henry (died 1714)

ADAMS, Thomas (1769-1845)

INVENTORIES

From 1530 to 1782 it was an obligation for every executor of a will to provide the probate court with an inventory of the deceased’s goods, together with their value. In the Diocese of Gloucester, Gloucestershire Archives have surviving inventories from 1587. However, not all inventories have survived as they were kept separately from the wills. They provide a huge amount of family and social information.

Towards the end of the 18th century they were very brief just listing ‘lumber and other goods’ and their value. Many of them accompanied administrations where the deceased had died intestate. Information from Fairford Wills was also transcribed, although not word by word.All the Gloucestershire inventories and wills are on line at www.ancestry.co.uk and FHS has transcribed copies of most of them.

See below for examples of an inventories, if you don’t know what the word is say it (in a Gloucestershire accent) and all will be come clear.

Click here Inventory William Early 1755

HURST, Walter (1702) Inventory

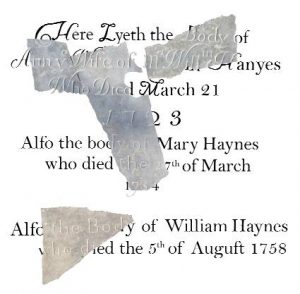

The surviving lettering matched perfectly the inscription on the grave of William and Ann Haynes and their daughter Mary who died in 1758, 1723 and 1754 respectively. Bigland records this as “On a flat stone in the South Aisle” of the church. It would appear that the Haynes stone was removed and broken up to be used as rubble during the reflooring of the church, possibly in 1854 when the church seating was replaced. Unfortunately this is by no means an isolated example of the length to which the Victorians would go to ‘beautify’ our churches. William Haynes had been a churchwarden for many years but even this didn’t stop his memorial being smashed up after less than 100 years.

The surviving lettering matched perfectly the inscription on the grave of William and Ann Haynes and their daughter Mary who died in 1758, 1723 and 1754 respectively. Bigland records this as “On a flat stone in the South Aisle” of the church. It would appear that the Haynes stone was removed and broken up to be used as rubble during the reflooring of the church, possibly in 1854 when the church seating was replaced. Unfortunately this is by no means an isolated example of the length to which the Victorians would go to ‘beautify’ our churches. William Haynes had been a churchwarden for many years but even this didn’t stop his memorial being smashed up after less than 100 years.

Between 1839 and 1847 Messrs Tovey were the millers at Fairford Mill. From 1889 until 1906 the Fairford Mill resident was Mr Richard Cole; a farmer, coal merchant and miller.

Between 1839 and 1847 Messrs Tovey were the millers at Fairford Mill. From 1889 until 1906 the Fairford Mill resident was Mr Richard Cole; a farmer, coal merchant and miller.

Also in the Lady Chapel is a chest tomb tomb with life-size stone effigies of Roger Lygon and his wife Katherine, widow of the grandson of John Tame. Beneath the floor of the chapel is a vault containing the remains of Sir Edmund Tame and his wives, Agnes and Elizabeth, all commemorated by a brass on the chapel’s north wall.

Also in the Lady Chapel is a chest tomb tomb with life-size stone effigies of Roger Lygon and his wife Katherine, widow of the grandson of John Tame. Beneath the floor of the chapel is a vault containing the remains of Sir Edmund Tame and his wives, Agnes and Elizabeth, all commemorated by a brass on the chapel’s north wall. These sculptures include a dragon, a lion, a dog, a sheep and, most charming of all, a boy in the act of climbing down from the parapet (right). In addition to these sculptures are figures of a more serious nature including the Christ of Pity at the west end of the church and four fierce guardians standing sentry at the four corners of the tower.

These sculptures include a dragon, a lion, a dog, a sheep and, most charming of all, a boy in the act of climbing down from the parapet (right). In addition to these sculptures are figures of a more serious nature including the Christ of Pity at the west end of the church and four fierce guardians standing sentry at the four corners of the tower. Among the grand and ancient tombs in the churchyard is a delightful stone sculpture of ‘Tiddles’, a much-loved Church cat who ‘guarded’ the church and its precincts from 1963 to 1980.

Among the grand and ancient tombs in the churchyard is a delightful stone sculpture of ‘Tiddles’, a much-loved Church cat who ‘guarded’ the church and its precincts from 1963 to 1980.

Bryworth Bridge near Fairford, 2006

Bryworth Bridge near Fairford, 2006

Farmor’s School opened as Fairford Free School on 24th November 1738. The school’s first schoolmaster was Jacob Kuffeler, a descendant of an ancient and prominent Dutch family. The building cost £543.8s, and consisted of a schoolmaster’s house and 2 classrooms with cellar and outbuildings including a brewhouse and a well in the rear yard. There had previously been several legacies to provide education in Fairford. In 1670 Lady Jane Mico founded a charity to provide apprenticeships for ” 4 poore Boys”, and in 1701 Mary Barker, daughter of Andrew Barker, Lord of the Manor of Fairford, left money for investment to raise funds for teaching poor boys to read and write. Later Elizabeth Farmor, Andrew Barker’s granddaughter, left £1000 in her will, specifically to build a school and pay a schoolmaster. The school originally had accommodation for 60 boys, aged between 5 and 12, and if Fairford children did not fill all the places, numbers could be made up from the surrounding villages. Boys could be “turned away” for bad behaviour, and left school to start work at the age of 12.

Farmor’s School opened as Fairford Free School on 24th November 1738. The school’s first schoolmaster was Jacob Kuffeler, a descendant of an ancient and prominent Dutch family. The building cost £543.8s, and consisted of a schoolmaster’s house and 2 classrooms with cellar and outbuildings including a brewhouse and a well in the rear yard. There had previously been several legacies to provide education in Fairford. In 1670 Lady Jane Mico founded a charity to provide apprenticeships for ” 4 poore Boys”, and in 1701 Mary Barker, daughter of Andrew Barker, Lord of the Manor of Fairford, left money for investment to raise funds for teaching poor boys to read and write. Later Elizabeth Farmor, Andrew Barker’s granddaughter, left £1000 in her will, specifically to build a school and pay a schoolmaster. The school originally had accommodation for 60 boys, aged between 5 and 12, and if Fairford children did not fill all the places, numbers could be made up from the surrounding villages. Boys could be “turned away” for bad behaviour, and left school to start work at the age of 12.

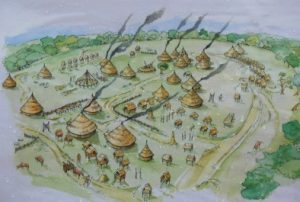

Evidence of fence posts and enclosures also exist. Within the settlement were the vestiges of a large number of four-post structures. These are thought to have been small grain stores as Spelt and Emmer wheat seeds where found in the post holes. Analysis of the Iron Age evidence continues.

Evidence of fence posts and enclosures also exist. Within the settlement were the vestiges of a large number of four-post structures. These are thought to have been small grain stores as Spelt and Emmer wheat seeds where found in the post holes. Analysis of the Iron Age evidence continues. Roman:

Roman: settlement at Horcott is one of the largest discovered in the region. There were two types of buildings; rectangular post-built halls and sunken-featured buildings or Grubenhausen (‘Grub Huts’). The sunken-featured buildings, consisting of a building raised on four large posts at each corner of a rectangular hole in the ground, may have been workshops or simple dwellings. The rectangular halls were thought to be houses.

settlement at Horcott is one of the largest discovered in the region. There were two types of buildings; rectangular post-built halls and sunken-featured buildings or Grubenhausen (‘Grub Huts’). The sunken-featured buildings, consisting of a building raised on four large posts at each corner of a rectangular hole in the ground, may have been workshops or simple dwellings. The rectangular halls were thought to be houses.